Despite gravity being the dominant force on large scales, the quantum nature of gravity remains elusive. Now, Berkeley Physics Professor Holger Müller’s group has built the most accurate instrument for measuring gravitational attraction between atoms and a small mass—enabling the search for deviations from Newtonian gravity due to quantum effects or hypothetical “fifth-force” dark energy.

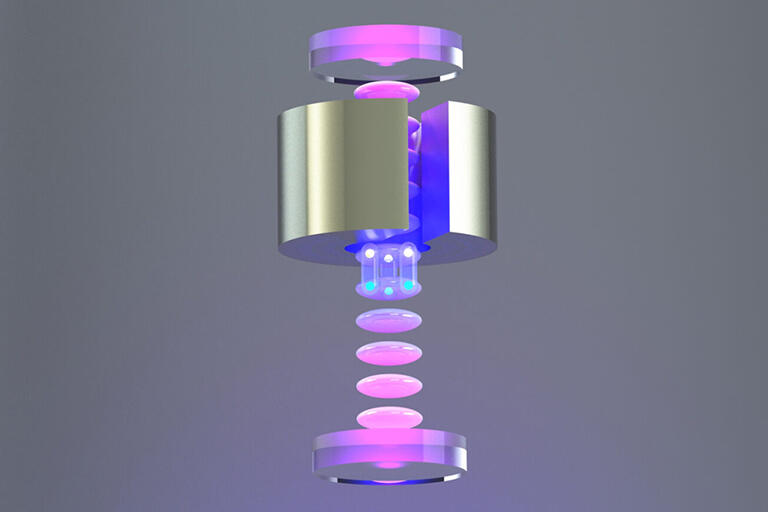

This novel lattice atom interferometer exploits both the particle-like and wave-like properties of matter. Clouds of laser-cooled cesium atoms in a vacuum chamber are immobilized for up to 70 seconds using a vertical optical lattice, which passes through the center of a hollow tungsten cylinder. Each atom is then excited into a quantum superposition, where the atom exists as partial wave packets in two locations simultaneously. The wave packet closer to the tungsten experiences more gravitational pull, changing its phase. When the lattice is turned off, measuring the phase difference between the wave packets reveals their difference in gravitational attraction. The researchers made these precise measurements for atoms above and below the tungsten to reject systematic errors.

“Gravity pushes down the atoms with a force a billion times stronger than their attraction to the tungsten mass, but the restoring force from the optical lattice holds them, like a shelf,” says Cristian Panda, a former postdoctoral fellow in Müller’s lab. “We then split each atom into two wave packets, so now it’s in a superposition of two heights. And then we take each of those two wave packets and load them in a separate lattice site, a separate shelf, so it looks like a cupboard. When we turn off the lattice, the wave packets recombine, and the quantum information acquired during the hold is read out.”

Using improved laser systems and cooling with their optical lattice, the team achieved four times better accuracy than previous interferometry measurements that used “free-fall” atoms. Their results were consistent with Newtonian gravity and placed limits on dark energy candidate particles.

This is a reposting of my magazine research highlight, courtesy of UC Berkeley’s 2024 Berkeley Physics Magazine.

Image Caption: Physicists at UC Berkeley split atoms into two wave packets (blue-white split spheres below cylinder) separated by microns that were then immobilized for many seconds in a vertical optical lattice (pink blobs). By recording the phase difference between wave packets that are closer and further to a tungsten mass (shiny cylinder), they were able to measure the weak gravitational attraction of the cylinder. (Cristian Panda/UC Berkeley)