Scientists across the nation are both fascinated by the work done at the Department of Energy’s national laboratories and could make important contributions to that work. Still, many of them – especially those at institutions historically underrepresented in the research community – don’t have the financial support or pathways they’d need to take part.

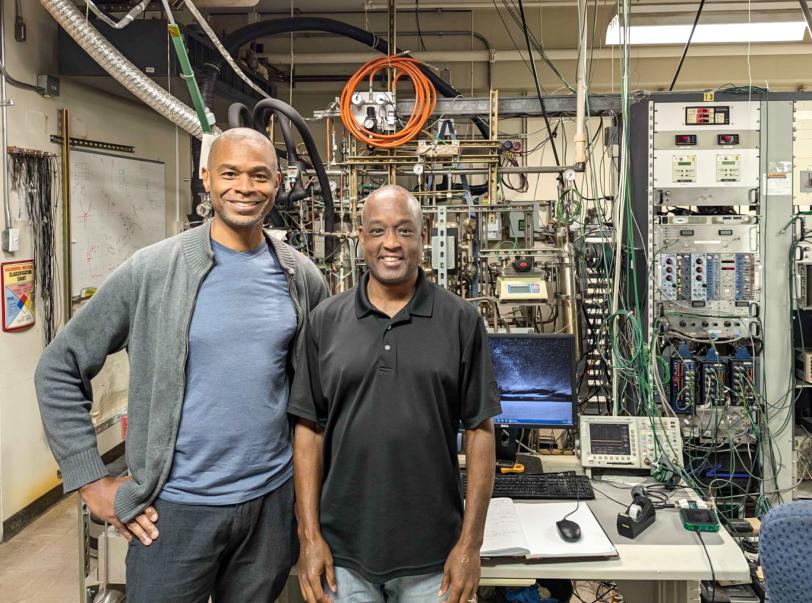

Such was the case for Southern University and A&M College’s Fred Lacy and Skyline College’s Kolo Wamba – but this summer both got a chance to learn from and contribute to research at DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory through DOE’s Visiting Faculty Program (VFP).

The program aims to enhance the faculty’s research competitiveness and STEM instruction, while helping to expand and diversify the workforce vital to DOE’s mission areas. VFP is designed for full-time faculty from schools that are not major research universities, known as R1 universities, or from historically black colleges or universities, said Hillary Freeman, SLAC’s STEM Education Program Manager. “Selected faculty members participate in research that they are interested in alongside SLAC scientists with similar interests,” Freeman said. “The goals include providing these faculty with access to world class research, learning new skills that can be brought back to the classroom to help develop the next generation of scientists, and perhaps moving their home institution towards an R1 status.”

Freeman noted that faculty can also bring students with them, which helps further the program’s goals.

“We need to create more awareness about the Visiting Faculty Program, which among other things gives our researchers the opportunity to leverage relationships with minority-serving institutions and the faculty who work there,” said Natalie Holder, chief diversity officer at SLAC. “It’s incredibly important that our researchers meet these visiting faculty, work alongside them, and exchange information.”

Enhancing microelectronic devices

Lacy, a professor and the chair of the electrical engineering department at Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, participated in the program to grow as a research engineer and person, as well as share the experience with Southern University’s students in the classroom.

Having no previous affiliation with DOE laboratories, Lacy established the partnership with SLAC through the VFP application process and ended up connecting with SLAC scientist Sander Breur in the Instrumentation Division of SLAC’s Technology Innovation Directorate (TID). “The Instrumentation Division consists of about 60 engineers, technicians, and scientists who fully focus on creating the technical capabilities that many of SLAC’s experiments require,” Breur said. “To conduct the required research, and help train the next generation of instrumentation experts, TID actively works on creating connections such as with the Visiting Faculty Program.”

This summer, Lacy tackled two projects to help develop microelectronic devices that may be included in future detector designs. The first, Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML), is led by SLAC engineers Dionisio Doering and Abhilasha Dave. The effort incorporates machine learning algorithms in microelectronic circuits to provide “edge computing,” enabling data to be analyzed closer to sensors and in real time instead of processing data remotely after collection. The main challenge of edge computing is having enough memory and hardware to perform and store the calculations.

“Researchers typically perform calculations by running really large, complex computer programs on large computers. If you reduce the number of lines of code and the digits representing each number in the calculations, then you can reduce the amount of necessary hardware,” said Lacy. “But how does that affect accuracy? What trade-offs are acceptable for particular applications? That’s what we’re exploring.”

In addition to the potential application of providing local, real-time data analysis for physics experiments, TinyML could be used in implanted or wearable devices for healthcare monitoring or in automotive systems for detecting drowsy drivers.

Lacy also worked towards developing application-specific integrated circuits that perform better in harsh environments for cryogenic and radiation experiments. This hardware-based Power Management through Integrated Capacitors (PMIC) project is led by SLAC engineers Hugo Hernandez, Aldo Perez, and Lorenzo Rota.

Currently these integrated circuits (or computer chips) need external capacitors to provide and store electric charge, but these capacitors are bulky and tend to be too contaminated by trace radiative impurities for some experiments. To address that issue, the PMIC project is exploring microfabrication techniques to integrate capacitors into the computer chips themselves. This summer, Lacy did preliminary materials testing of small capacitors in super cold environments.

“Working with both SLAC groups was a fabulous experience,” said Lacy. “I plan to continue the TinyML project at my home institution and will start involving students. I also plan to teach them the basics of the PMIC project, so they can immediately make an impact when I bring them to SLAC, hopefully next summer. But I’ll also mention my VFP experience to students in all of my classes to open their minds to different career options, because the national labs aren’t on their radar the way Fortune 500 companies are.”

Improving xenon purity monitoring

Wamba, a physics and astronomy professor at Skyline College in San Bruno, California, has a longstanding relationship with SLAC – including earning a PhD in applied physics at Stanford University based on performing research for the EXO-200 experiment, the predecessor of nEXO, with Martin Breidenbach, a professor emeritus at SLAC.

The nEXO project is a proposed international nuclear physics experiment that will use an enormous tank of liquid xenon to search for neutrinoless double beta decay. If this rare and hypothetical process is discovered, it would prove that neutrinos are their own antiparticles and help physicists understand various mysteries of the universe, including why there is more matter than antimatter in the universe.

Wamba formally joined the nEXO collaboration as a faculty member in 2021, and has previously brought students to SLAC through the DOE’s Research Traineeships to Broaden and Diversify pilot program. Rather than continuing this work through Skyline College’s new RENEW program, Wamba applied to VFP.

“The VFP is a good fit for supporting my nEXO research because the funding program is limited to summer, so it doesn’t conflict with my teaching responsibilities,” Wamba said.

This summer, Wamba worked with SLAC physicist Peter Rowson on nEXO’s xenon purity monitor (XPM) system, a custom-built apparatus used to determine the chemical purity of a liquid xenon sample after it has been exposed to materials that could generate impurities. Originally, Wamba planned to run the XPM a “bunch of times,” acquiring and analyzing various data sets under different conditions.

Although troubles with a faulty power supply got in the way of those plans, there was a silver lining. “We didn’t get to run the xenon purity monitor as many times as I was hoping this summer,” Wamba explained. “But on the flip side, this gave me an unexpected opportunity to construct hardware that simulates the XPM so we can characterize its systematic errors. I wasn’t even thinking of doing that at the beginning.”

Wamba programed a waveform generator to create a “ground truth” signal that would mimic the output of the XPM. This hardware simulator was then used in place of the XPM, running the signal through the entire system and analysis chain. By comparing the resulting signal with the ground truth one, the systematic errors were characterized, using fewer assumptions than a previously planned software simulator.

Wamba plans to reapply to the Visiting Faculty Program and bring at least one student next summer to do other nEXO research projects. “I plan to use project-based learning where I guide students and teach them whatever they need as it comes up.”

Holder was happy to hear that Lacy and Wamba both intend to bring students to SLAC. “The goal for the future is to have the visiting faculty bring some of their students along with them, and to ignite that interest in their students to come back eventually to study, maybe at Stanford while pursuing their PhDs, and then eventually to become our colleagues as staff, researchers, faculty, and maybe even one day as a lab director,” Holder said.

Lacy and Wamba were supported by the DOE’s Visiting Faculty Program, a component of DOE’s Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists program. SLAC researchers were supported in part by the DOE Office of Science.

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

This is a reposting of my news feature courtesy of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.