The bright yellow forklift crept forward, gracefully maneuvering the 20-ton steel tank through the entrance of Etcheverry Hall’s basement with only two millimeters to spare. Relying on the expertise of Berkeley Lab riggers, this tight squeeze was by design to maximize the size of the outer vessel of the Eos experiment.

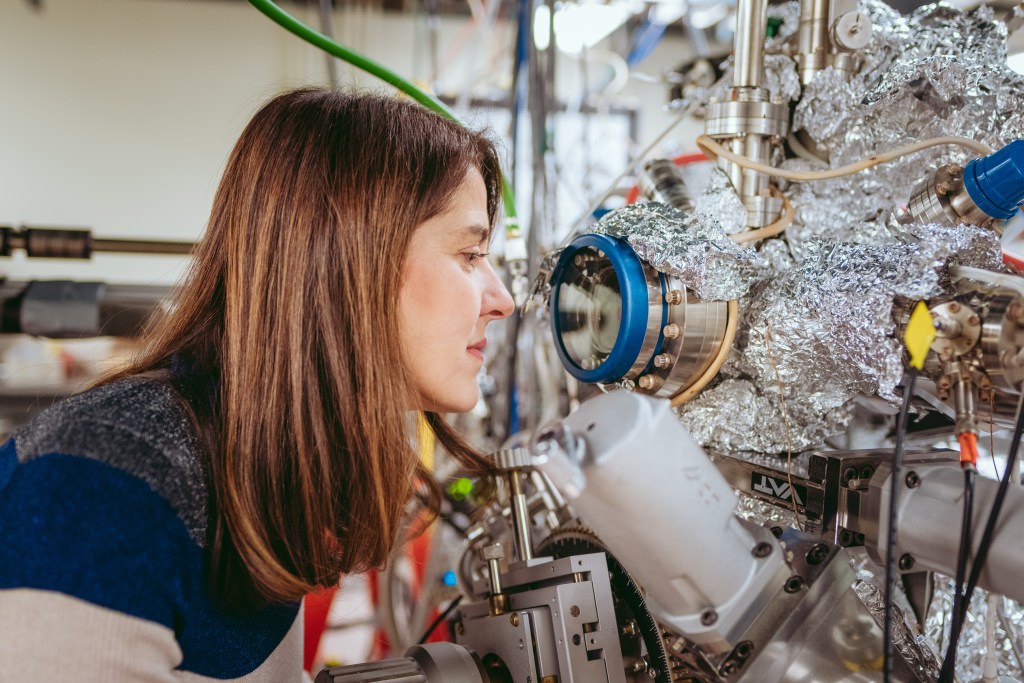

“Named for the Titan goddess of dawn, Eos represents the dawn of a new era of neutrino detection technology,” says Gabriel Orebi Gann, a Berkeley Physics associate professor, Berkeley Lab faculty scientist, and the leader of Eos, an international collaboration of 24 institutions jointly led by UC Berkeley Physics and Berkeley Lab Nuclear Science.

Neutrinos are abundant, neutral, almost massless subatomic “ghost particles” created whenever atomic nuclei come together or break apart, including during fusion reactions at the core of the Sun and fission reactions inside nuclear reactors on Earth. Neutrinos are difficult to detect because they rarely interact with matter—about 100 trillion neutrinos harmlessly pass through the Earth and our bodies every second as if we don’t exist.

Berkeley researchers are using Eos as a testbed to explore advanced, hybrid technologies for detecting these mysterious particles.

“While at Berkeley, we’re characterizing the response of the detector using deployable optical and radioactive sources to understand how well our technologies are performing. And we’re developing detailed simulations of our detector performance to make sure they agree with the data,” says Berkeley Physics Postdoctoral Fellow Tanner Kaptanoglu. “Once we complete this validation, we hope to move Eos to a neutrino source for further testing.”

Ultimately, the team hopes to use their experimental results and simulations to design a much larger version of Eos—named after the Titan goddess Theia, mother of Eos—to realize an astonishing breadth of nuclear physics, high energy physics, and astrophysics research.

The Eos collaboration is also investigating whether these technologies could someday detect nuclear security threats, in partnership with the funding sponsor, National Nuclear Security Administration.

“One nonproliferation application is using the absence of a neutrino signature to demonstrate that stockpile verification experiments are not nuclear,” says Orebi Gann. “A second application is verifying that nuclear-powered marine vessels are operating correctly.”

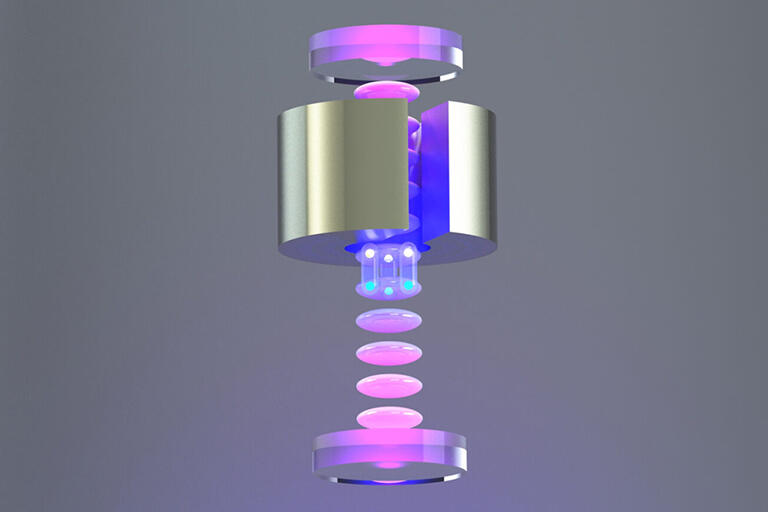

Unique, hybrid neutrino detector

Like a nesting doll, Eos comprises several detector layers. The inner layer is a 4-ton acrylic tank, filled in stages during testing with air, then deionized water, and finally a water-based liquid scintillator (WbLS).

The barrel of this inner vessel is surrounded by 168 fast, high-performance, 8-inch photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) with electromagnetic shielding. Attached above the vessel are two dozen 12-inch PMTs. And attached below it are three dozen 8-inch “front-row” PMTs, with another dozen 10-inch PMTs below them.

In January, this detector assembly was gently lowered inside the 20-ton steel outer vessel, with Berkeley Physics Assistant Project Scientist Leon Pickard operating the crane as other team members anxiously watched.

“The big lift this was nerve-wracking. More than a year’s worth of work, dedication, and time from lots of people and then I was lifting it all together into the outer tank,” describes Pickard. “I knew the Berkeley Lab riggers taught me well so I was confident, excited, and definitely nervous.”

The buffer region between the acrylic and steel vessels is filled with water, submerging the PMTs. The outermost Eos layer is a muon tracker system consisting of solid scintillator paddles with PMTs.

By combining several novel detector technologies, Eos measures both Cherenkov radiation and scintillation light simultaneously. Its main challenge is to separate the faint Cherenkov signal from the overwhelming scintillation signal.

When neutrinos pass through Eos, one very occasionally interacts with the detector’s water or scintillator, transferring its energy to a charged particle. This charged particle then travels through the medium, emitting light that is detected by the PMTs.

When the charged particle travels faster than the speed of light in the medium, it creates a photonic boom—similar to the sonic boom created by a plane traveling faster than the speed of sound. This cone of Cherenkov light travels in the direction of the charged particle, making a ring-like image that is detected by the PMTs. In contrast, the scintillation light emits equally in all directions. Reconstructing the pattern of PMT hits helps distinguish between the two signals.

In addition to topological differences, Cherenkov radiation is emitted almost instantaneously in a picosecond burst, whereas scintillation light lasts for nanoseconds. The PMTs detect this time difference.

Finally, the observable Cherenkov radiation has a longer, redder wavelength spectra than the bluer scintillation light, which inspired the creation of dichroic photosensors that sort photons by wavelength. These dichroicons consist of an 8-inch PMT with a long-pass optical filter above the bulb and a crown of short-pass filters surrounding it. A dozen of the 8-inch, front-row PMTs attached to the bottom of the inner vessel are dichroicons. The concept for these novel photosensors was developed under the leadership of Eos collaborator Professor Joshua Klein, with Kaptanoglu playing a central role as part of his PhD thesis at the University of Pennsylvania.

If the light’s wavelength is above a certain threshold, a dichroicon guides Cherenkov light onto the central PMT. If the light is below that threshold, it passes through and is detected by the 10-inch, back-row PMTs.

“You effectively guide the Cherenkov light to specific PMTs and the scintillation light to other PMTs without losing light,” says Orebi Gann. “This gives us an additional way to separate Cherenkov and scintillation light.”

Another unique thing about Eos is its location.

“Although Eos is a Berkeley Physics project, the Nuclear Engineering department let us work in their space in the Etcheverry basement,” says Orebi Gann. “It’s unusual to work across departmental boundaries in this way. It’s a sign of how great and supportive Nuclear Engineering has been.”

Team work

Delivering the outer vessel into the building wasn’t the only tight squeeze—the Eos installation was temporally and physically tight.

Neutrino experiments often struggle to get their steel tanks manufactured, so everyone was excited last June when the tank headed towards Berkeley. Unfortunately, Orebi Gann received an email the next morning saying the tank was destroyed in a non-injury accident when the truck collided with an overpass in Saint Louis. After immediately calling her sponsor with the bad news, she mobilized.

“I started sweating. They would have killed our three-year project if we had to wait for the insurance claim,” says Orebi Gann. “Luckily, Berkeley Lab Nuclear Science Division Director Reiner Kruecken and others were really supportive, and we had enough contingency in the budget to buy another one. Within two weeks, we were under contract for a replacement. And the steel tank arrived three months later.”

Despite this delay, the collaboration assembled the detector, acquired and analyzed the data, and finished developing the detector simulations during the last year of funding.

“That’s the biggest setback you can have—your tank is crumpled. But with prudent planning, preparation, and scheduling agility, we were able to get right back on track,” says Pickard, also the installation manager.

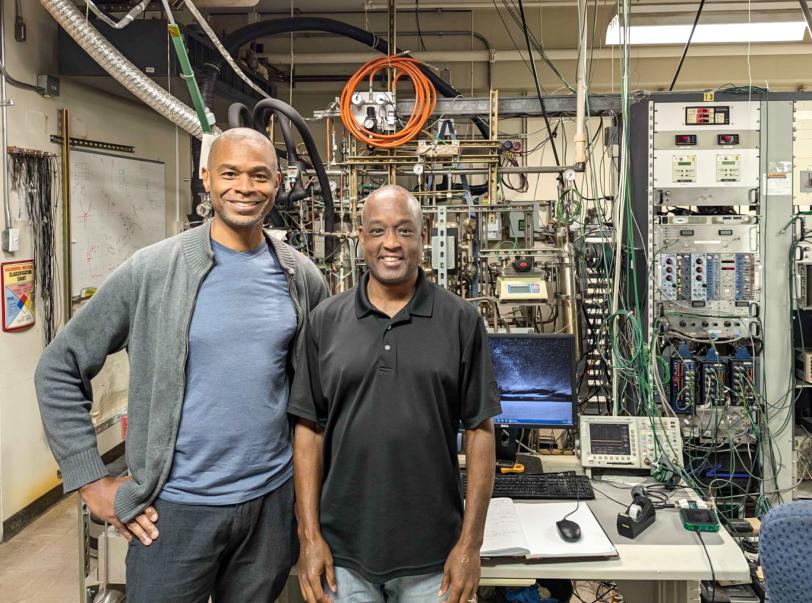

In addition to Orebi Gann, Pickard, and Kaptanoglu, the Berkeley Physics installation team included former Project Scientists Zara Bagdasarian, Morgan Askins, and Guang Yang, Junior Specialist Sawyer Kaplan, graduate students Max Smiley, Ed Callaghan, and Martina Hebert, and undergraduate students Joseph Koplowitz, Ashley Rincon, and Hong Joo Ryoo. They were assisted by Berkeley Lab Staff Scientist Richard Bonventre, Senior Scientific Engineer Associate Joe Wallig, mechanical engineer Joseph Saba, and machinist James Daniel Boldi.

Given the tight timeline and limited space, another installation challenge was where to put all the detector components. Eos collaborators across the country coordinated to bring everything in at just the right time, fully tested and ready to go for the build.

“Some of the deliveries stayed temporarily at Berkeley Lab. Gabriel let us use her office to store hundreds of PMTs for a while. And the Nuclear Science folks were phenomenally accommodating, allowing us to store muon paddles, PMTs, and other parts on the Etcheverry mezzanine,” Pickard says. “We played a huge game of Tetris to get the detector put together.”

Data acquisition and reconstruction

Once assembled, Eos acquired and analyzed data in three phases.

This March, it measured “first light” by flashing a blue LED into an optical fiber that points into the detector and then detecting this light with the PMTs. During initial tests, the inner vessel contained air while ensuring all the detector channels were working and the PMTs were measuring single photons.

Next, they filled the inner tank with optically-pure deionized water and took data using various radioactive sources, optical sources, a laser injection system, and cosmic muons to fully evaluate detector performance. During this phase, Eos operated as a water Cherenkov detector.

“In a water Cherenkov detector, you have only Cherenkov light so you can do a precise directional reconstruction of the event. This helps with particle identification at high energies and background discrimination at low energies,” says Kaptanoglu, also the commissioning manager who helps identify the data needed. Among his other roles, he co-leads the simulations and analysis team with Marc Bergevin, a staff scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Lab.

Lastly, the researchers turned Eos into a hybrid detector by injecting into the water a water-based liquid scintillator, which was supplied by Eos collaborator Minfang Yeh at Brookhaven National Laboratory. This allowed the team to explore the stability and neutrino detection capabilities of the novel scintillator. Adding WbLS improves energy and position reconstruction, but it makes event direction reconstruction difficult. A key goal was to show that Eos could still reconstruct the event direction with the WbLS—proving WbLS as a viable, effective, and impressive neutrino detection medium.

“Our hybrid detector gives us the best of both worlds. We measure event directionality with the Cherenkov light, and we achieve excellent energy and position resolution and low detector thresholds using the scintillation light,” says Kaptanoglu, “But by combining Cherenkov and scintillation, we get additional benefits. For example, we can better tell what type of particle is interacting in our detector— whether it’s an electron, neutron, or gamma.”

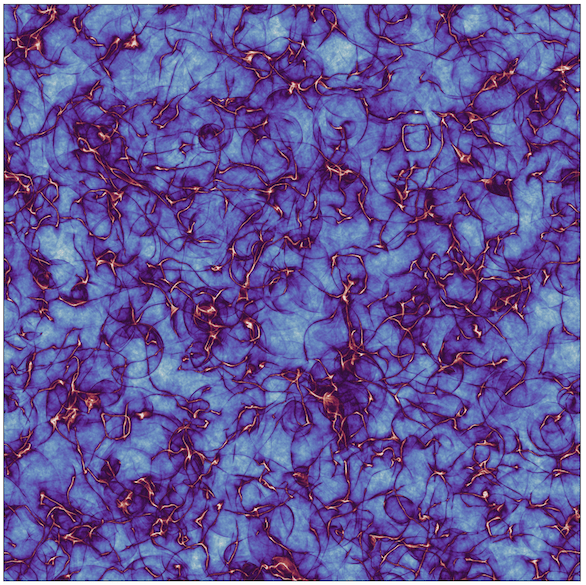

Eos data analysis combines traditional likelihood and machine learning algorithms to reconstruct events. These novel reconstruction algorithms simultaneously use the Cherenkov and scintillation light, finding a ring of PMTs hit by the Cherenkov light on top of the much larger isotropic scintillation light background. The team also compared the two methods to see if machine learning gave them any advantages.

“Our goal was to show that we can do this hybrid reconstruction and that we can simulate it well to match with the experimental data,” says Kaptanoglu.

Their simulations entail microphysical modeling of every aspect of the Eos detector, characterizing in detail how the light is created, propagated, and detected. In addition to producing cool 3D renderings of the detector, Eos simulations will be used to help design future neutrino experiments.

“Our Monte Carlo simulations make predictions, and we compare those to our experimental data. That allows us to validate and improve the Monte Carlo simulations,” say Orebi Gann. “We can use that improved Monte Carlo to predict performance in other scenarios. It’s the step that allows us to go from the measurements we make at Berkeley to predicting how this technology would perform in different application scenarios.”

Next steps

Although their three-year project recently completed, Orebi Gann has applied for another three years of funding to extend Eos testing at Berkeley.

If funded, the team plans to explore different WbLS cocktails and various photosensor parameters. They are also considering upgrading to custom electronics.

During the additional three years, the team would also devise a plan for moving Eos to a neutrino source if they get follow-on funding. A likely location is the Spallation Neutron Source at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. This facility basically smashes neutrons into a target to produce a huge number of neutrinos.

“Moving Eos to the Spallation Neutron Source would allow us to demonstrate that we can see neutrinos with this technology, in a regime where it’s not as subject to the low energy backgrounds that make reactor neutrino or fission neutrino detection challenging. It’s a step on the road,” says Orebi Gann.

According to Orebi Gann, the next step after that would be to move Eos to a nuclear reactor to prove it can detect neutrino signals in an operational environment with all relevant backgrounds.

Theia fundamental physics

However, the ultimate plan is to use Eos experimental results and simulation models to guide how to design Theia-25 (or Theia-100), a massive hybrid neutrino detector with a 25-kiloton (or 100-kiloton) WbLS tank and tens of thousands of ultrafast photosensors.

Orebi Gann is a lead proponent of Theia, a Berkeley-led “experiment in the making.” If funded, Theia will likely reside at the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) located in an abandoned gold mine in South Dakota.

Theia has two potential areas of fundamental physics research. The first is understanding the neutrinos themselves.

“In particle physics, we don’t know of any fundamental property that differentiates neutrinos from antineutrinos, so they could in fact be incarnations of the same particle,” she explains. “Understanding their fundamental properties and how they differ could, for example, help explain how the Universe evolved, including offering insights into why it is dominated by matter.”

The second area of fundamental physics research uses the very weakly interacting neutrinos to probe the world around us.

“A large WbLS detector would enable us to look at solar neutrinos, supernova neutrinos, geo-neutrinos naturally produced in the Earth, and a vast array of other measurements,” says Orebi Gann. “For example, solar neutrinos would give us a real-time monitor of the Sun.”

“What’s interesting about Theia is the breadth of its program. I can go on for an hour about the physics of Theia,” Orebi Gann adds. “I think Eos, and the other R&D technology demonstrators around the world, will allow us to realize something like Theia, which would have a rich program of world leading physics across nuclear physics, high energy physics, and astrophysics.”

This is a reposting of my magazine feature, courtesy of UC Berkeley’s 2024 Berkeley Physics Magazine.